Introduction to the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas

Ch 2: Being: Metaphysical Study

II. THE METAPHYSICAL NOTION OF BEING

The object of metaphysics, we have said, is being. This is true - truer, indeed, than appears on the surface. For, formally speaking, the object of metaphysics is not being considered as the first object of thought, or being whose conception is the first notion of the intellect. The object of metaphysics lies deeper, and to reach it the mind must have recourse to the third degree, the metaphysical degree, of abstraction, in which being is considered in utter separation from matter. Only then does the mind apprehend being formally; only then, that is, does the mind apprehend being as being, or being as such.3 And this is the object of metaphysics: being as being, or being as such, prescinded from this or that mode of it.

The distinction just made is capital; the distinction, I mean, between being as the object of metaphysics and being as the first and most universal object of thought. It takes a while, even a long while, to rise to this distinction, to the level of metaphysical being. By nature the human intellect inclines rather to the things of the sensible world; the utterly immaterial is not its connatural milieu. And though, as we have seen, it necessarily conceives of everything and hence of sensible things as beings, the being it first finds in them is not that of metaphysics, unparticularized and matter-free, but that of the physical kind, particularized and matter-bound. There is, to be sure, in this common knowledge of sensible things a rudimentary grasp and awareness of being, but not of being as being, since in this order of knowledge being is not yet prescinded, or lifted, from its particularities. In short, the experience of being that fashions routine thought, and bases even the sciences, is all on the prephilosophical (i.e. premetaphysical) level.

Closer, but only closer, to the metaphysical state of affairs is the concept of being that emerges from its universalization on the lines of logic. Go back to the familiar experience of being alluded to a moment ago, the objects of daily acquaintance. It is relatively simple to subsume these objects under notions that are more and more universal, as in the Tree of Porphyry, where we find the series: man, animal, living body, body, substance. As it stands, however, the series is still open; for there is something still more comprehensive than substance, namely being, which comprehends everything and hence closes the series. Thus the mind has arrived at the logical universal of being. What it has done is to make a "total" abstraction of being, which means the abstraction of a logical whole from its inferiors. The notion thus derived is both most universal and, for that reason, most undetermined, containing as it does, though but implicitly, all the differences of being in its endless variety.

Because of the abstraction involved in its formation, this generalized notion of being already implies a measure of philosophical reflection, but the reflection is still pitched to the level of common understanding. More important, the notion, because of its universality, is sometimes mistaken for the formal or metaphysical concept of being which we shall examine forthwith, a confusion fatal to the grasp of metaphysics in the traditional sense. That it is a confusion should be evident, if not from what has gone before, then from what is to follow; which is by way of saying that the foregoing considerations have been but preliminary to the point in hand, the metaphysical notion of being. Having dwelt on what this notion is not, we are more ready to set out what it is; and the exposition, in one form or another, will run the rest of the chapter.4

A serviceable, though far from adequate cue can be found in the very name "being," which translates the Greek participial noun to on and its Latin derivative ens.5 Unfortunately, the English "being" does not do full justice to its Greek and Latin counterparts, at least in their metaphysical connotation. So that instead of "being," it would be more exact to translate "the something which is." This rendition points at once to two aspects of every being: a subject or receptor, "the something," and the actuation or determination of the subject, indicated by "which is." Metaphysically, the first aspect signifies essence (essentia); the second, existence (existentia or esse). Being, accordingly, is something whose actuality, or proper determination, is to exist.The notion of being necessarily implies both aspects. Essence cannot be conceived except in relation to existence, and existence in turn calls for determination by essence. Still, it is possible when thinking of being to give attention more to one than to the other. This becomes clear when it is remembered that the word "being" serves both as noun and as verbal (participial noun). When being, the word, functions or is understood as a noun, its primary reference is to essence (res); what it says, in effect, is that being is "what is," yet not so as to exclude the relation to existence which, as we have indicated, is ever implied in the notion of being. As a verbal, on the other hand, being stresses existence; what it then tells, properly, is that being is "what exists," but again the other aspect is not eliminated, since existence is always correlative with essence, always the existence of something. So that, once more, being as we conceive of it comes forth as a composition of two inseparable aspects, essence and existence. However, the qualities of this composition together with its far-reaching implications are, at this stage of our study, far from told; we shall see to that later.6

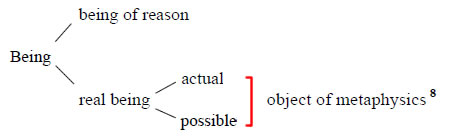

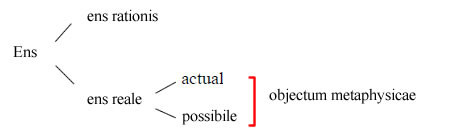

One point should, however, be cleared up now, namely, the metaphysical meaning of existence. If the being which the metaphysician studies includes the aspect of existence, obviously a thing must be affiliated with existence to come under the object of metaphysics. But what kind of existence? Primarily, "being as being" (the object of metaphysics) signifies existence (esse) in its immediate sense of real and actual existence: ens actuale, as the expression goes. But "being as being" is not limited to this; for also to be included is possible being: ens possibile, i.e. anything capable of entering the world of concrete existence. Thus, whatever has been, or is, or will be, or could really be, under whatever mode or manner, is comprised under the object of metaphysics, yes even that which is affined to the concrete order of things by way of privation or negation.7 One thing only is debarred, the being of reason (ens rationis), which is the subject of logic. The true being of reason does, no doubt, have a foundation in reality, yet its very nature is such that it cannot, as a being of reason, exist in reality; it can only exist in the mind conceiving it. Consequently, it fails of inclusion in the metaphysician's domain, the order of concrete existence, actual or possible.

This can be schematized:

We come then to another side of the problem of being; but first, a word in passing. Examined so far in the present chapter have been being and its notion for their metaphysical meaning according to St. Thomas; that is to say, examined and defined has been the formal object of metaphysics. This is only one step in the study of being, but the step that sets the course for the whole of it. Thus, while there is indeed more to metaphysics than the settlement of its formal object, there is nothing more critical; for the formal object, or rather one's view of it, shapes the rest of it. So that in committing ourselves to the view of being that emerges from the foregoing paragraphs, we have subscribed to a line of development for the whole of metaphysics. Also, further reflection, the exact determination of the formal (metaphysical) notion of being is not only a necessary preliminary to the science, but has always been a thorny problem for the philosopher. Sooner or later he must ask: what is being? and sometimes, perhaps often, he has answered inadequately if not erroneously. Contemporary thought, on the whole, while exploiting the concrete or existential side of things, is in general disdainful of essential being. Tending to the other extreme are philosophers of the not too distant past by whom being is all but identified, if not actually so, with essence, to the exclusion or neglect of existence. For St. Thomas, as we shall have frequent occasion to repeat, being is neither essence alone nor existence alone but a composite of the two: an essence actuated by its ultimate perfection, existence.9

Footnotes

3 It is all the same whether we say "being as formally apprehended," "being as such," or "being as being." -- [Tr.]4 Cf. Text XII, "Concerning Being and Essence," p. 276.

5 French: etre, which, as the author remarks in the French text, were better read as le étant, truly a more felicitous rendition of the Latin ens; its allusion, however (being "is" or "isses"), is practically impossible to import into the English being. Perhaps the best we can do is to hyphenate, i.e. to give it as be-ing, with the thrust on the second syllable. -- Translator's note.

6 Namely in chapter 7, Essence and Existence

7 This view, however, that the being which constitutes the object of metaphysics includes possible being, is not unanimously held. See, for example, W. Norris Clarke, S.J., "What Is Really Real?" in Progress in Philosophy (Philosophical Studies in Honor of the Rev. erend Charles A. Hart), pp. 61-9o; ed. by James A. McWilliams (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Co., 195 5). -- [Tr.]

8

9 The metaphysician, to be sure, knows of a being that is not a composite but an identity of essence and existence; yet even this being is not conceived by us except on the lines of a composite. -- [Tr.]