Introduction to the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas

Ch 2: Being: Metaphysical Study

IV. THE DOCTRINE OF ANALOGY

Preliminary note: analogy in St. Thomas and his commentators. To give a clear-cut view of the Thomistic teaching on analogy is not an easy thing to do. The considerable difficulties encountered stem in part from the fact that nowhere does St. Thomas develop the subject in full, nor in its own behalf. Thus, while he frequently speaks of analogy, it is always in application to some other point at issue. Such as it is, therefore, his teaching lies scattered over isolated treatments which, even in sum, do not afford a full exposition, to say nothing of the consequent problem of reconciling passage with passage so as to get a consistent body of doctrine. In this matter, then, the mere unraveling of his text suffices even less than it does elsewhere, and the only satisfactory alternative appears to be reconstruction of his thought, with, of course, the systematic interpretation that reconstruction supposes.

Interpretive works of this kind have been provided by the great commentators of St. Thomas. They give a doctrine of analogy such as St. Thomas himself might have given - or did give, in embryo. The prime specimen, without a doubt, is Cajetan's De Nominum Analogia,12 which can boast of a veritable school, so great has been its influence. A fellow commentator of rank, John of St. Thomas, does little more, in re, than reproduce Cajetan.13 Between them they have the interpretation of analogy most commonly accepted by present-day Thomists. A certain number, however, professing themselves more faithful to the letter of St. Thomas, prefer Sylvester of Ferrara, who parts somewhat from his fellows.14

But whatever their own differences, Thomistic masters are as one in naming the principal adversary, Duns Scotus, defender of the univocity of being, or at any rate of its concept. Likewise disputed is Suarez who, in true Suarezian style, had taken a middle course, thus pleasing neither side. It is not for an introductory study such as this, however, to debate one school against another. Below, therefore, is simply an account of the doctrine of analogy such as, in our opinion, has the strongest support.15

1. The Meaning of Analogy

Popular as well as scientific thought abounds in the use of analogy. Things, as a matter of course, are said to be analogous when they bear some likeness to each other. Philosophically speaking, however, not every likeness makes an analogy, and we shall see presently what is required for this.

In the Aristotelian scheme, analogy is first viewed under a theory of general logic, the theory of predication, which has only to be applied to the notable case of being. St. Thomas concurs in this approach, for he, too, generally introduces analogy as a mode of logical predication, the mode that is neither univocal nor equivocal but in between, analogical. These distinctions have therefore to be explained. "Univocal" describes the term (word and concept) which is said of things (its inferiors) according to the same meaning in every case. "Equivocal," on the other hand, designates a term or word (never a concept) which is applied to things according to a meaning that is wholly different from one to the next. Thus, in "Peter is a man" and "Paul is a man" the term "man" is univocal; there is identity of meaning. But in "the bark is peeling" and "the bark awoke me" the term "bark" has obviously two completely different meanings. Between complete identity and complete diversity there is a middle ground, occupied by the "analogous" term (word and concept), which is said of many (its inferiors) according to a meaning that is partly the same and partly different in each case. So, in "intellectual vision" and "bodily vision" the term "vision" is neither univocal nor equivocal but analogous. On which general topic St. Thomas expresses himself thus:

It is evident that terms which are used in this way analogically] are intermediate between univocal and equivocal terms. In the case of univocity one term is predicated of differ- ent things according to a meaning [ratio] that is absolutely one and the same; for example, the term animal, predicated of a horse and of an ox, signifies a living sensory substance. In the case of equivocity the same term is predicated of various things according to totally different meanings, as is evident from the term dog, predicated both of a constellation and of a certain species of animal. But in those things which are spoken of in the way mentioned previously [i.e. analogically], the same term is predicated of various things according to a meaning that is partly the same and partly different: different as regards the different modes of relation, but the same as regards that to which there is a relation.16

This, then, is our preliminary finding: that analogy is an intermediate mode of predication, lying between the univocity of a logical universal and the equivocation of certain terms to which convention assigns disparate meanings. But this is not the whole of it. Analogy, in its further discrimination, denotes a relation, an agreement, a proportion - terms, all, which tell of one or the other aspect. In general, however, every analogical denomination bespeaks a relation, or relations, between certain things. And where there is relation there is community or a common element which, in the case of analogy, may be considered from two sides: that of the analogates, that is, the things which are related to each other, or that of the concept in which the mind seeks to unify the diversity confronting it. In addition, analogy always implies order of some kind, and order presupposes a unifying principle. So that, in sum, true analogy requires 1)a plurality of things z)related to each other 3) according to a certain order and 4)brought together by the mind under one, unifying concept.

2. Division of Analogy

Both St. Thomas in a much-cited passage 17 and Cajetan in his distinguished work 18 propose a threefold division of analogy, though not all three in identical terms. Thus, what St. Thomas calls "analogy according to being but not according to concept," Cajetan designates more simply as "analogy of inequality." 19 Actually, however, this analogy by whatever terminology is more properly a case of univocal predication, except that the concept in question is realized more perfectly in one thing than in another (hence the "inequality" of Cajetan). So, in the ancient example, the generic concept "body" is univocal but realized unequally in the two species of body: corruptible and incorruptible. Since, as has already been intimated, being is not predicated univocally, this kind of analogy does not serve in metaphysics. What is left then are the two basic types: analogy of attribution (St. Thomas: of proportion) and analogy of proportionality.

a) Analogy of attribution. This is the analogy about which Aristotle is most explicit, applying it even to the special case of being considered as the object of metaphysics. The unity of the analogous concept stems, in this case, from the fact that all the analogates (except the principal) are referred to one and the same term (principal analogate). Thus, to take the classical example, food, medicine, and complexion are said to be healthy (puristically: "healthful") for the reason that food, medicine, and complexion are all related to health, the first two as causing or contributing to it, the third as indicative of it. Properly speaking, however, health is found only in the animal nature.

More precisely, in the analogy of attribution there is always a primary (or principal) analogate (or analogue), in which alone the idea, the formality, signified by the analogous term is intrinsically realized. The other (secondary) analogates have this formality predicated of them by mere extrinsic denomination. Health, to come back to our example, exists formally and intrinsically, i.e. really and truly, only in the animal. Yet food, medicine, and complexion are rightfully called healthy, but by reason of some association with health, hence by reason of something extrinsic to themselves, the health of the animal. Thus, to put them in order, the characteristics of the analogy of attribution are these. First, the form (ratio) in question is one, numerically one, and occurs intrinsically in one analogate only. Second, this form must figure in the definition of the other analogates. Third, the secondary analogates cannot be represented by a single concept but only by a plurality of concepts, among which there is, however, a certain inter-implication. Finally, it is worth adding that among the secondary analogates there is also a kind of gradation, according to their propinquity to the primary analogue.

b) Analogy of proportionality. It will be remembered that in the analogy of attribution the (secondary) analogates are unified by being referred to a single term, the primary analogue. This marks a basic contrast with the analogy now under consideration, that of proportionality; for here the analogates are unified on a different basis, namely by reason of the proportion they have to each other. Example: in the order of knowledge we say there is an analogy between seeing (bodily vision) and understanding (intellectual vision) because seeing is to the eye as understanding is to the soul. We may, as St. Thomas himself does, represent this analogy in mathematical form, thus: seeing : eye = understanding : soul so long as we do not forget that the mathematical representation is only an illustration, not to be taken literally. Metaphysical analogy is not reducible to mathematical proportion, as should be apparent even from our example, there being no absolute equality (or identity) between the two relations in question.

What distinguishes this analogy most sharply from the analogy of attribution is that the nature or idea (ratio) signified by the analogous term occurs intrinsically and formally in each of the analogates. Consequently, even though there may be a primary analogate, the nature in view is not, as in attribution, possessed solely by this analogate. And whereas in attribution analogy is founded on the extrinsic relation of the secondary analogates to the primary, in proportionality its foundation, its ontological basis, lies deeper, consisting in the inner community among things that are yet different and go by different names. Thus, in our earlier example, "seeing" and "understanding" are not the same thing, but both are truly and formally acts of knowledge. Furthermore, since the nature spoken of exists intrinsically in all the analogates, the definition of one analogate does not necessarily imply the definition of the others. I can, for instance, define "seeing" without reference to "understanding." On the other hand, because of their inner community all the analogates can be represented by a single concept, as, once more, seeing and understanding by the one concept "act of knowledge." Any such concept, however, will not represent the analogates adequately, nor will it have the perfect unity of the univocal concept. In the next heading we shall deal expressly with this matter, the unity of the analogous concept. At the moment we have a more general item still to report, the kinds of proportionality.

St. Thomas, in a passage which constitutes the principal reference for the doctrine of analogy,20 divides proportionality into two kinds: metaphorical and proper. In the analogy of proper proportionality, which we have explained, the nature signified by the analogous term is truly and formally realized in each of the analogates - a point we emphasized. In metaphorical proportionality, on the other hand, the nature exists properly (and literally) in one analogate only, and figuratively (or improperly) in the others. So, for example, "smiling" is properly said of man only, but is predicated figuratively of meadow. The analogous notion may, however, be acknowledged to exist intrinsically in the meadow as well as in man, since a meadow is said to be smiling by reason of an intrinsic quality. As for terminology, metaphorical analogy may also be called improper and mixed: improper by contrast to proper, and mixed because it combines a proper meaning of the analogous notion with one or more improper (i.e. figurative) ones. Metaphorical analogy is, moreover, part and parcel of daily speech, and theology itself employs it well and abundantly. But in metaphysics it has no role; it is not a metaphysical analogy.

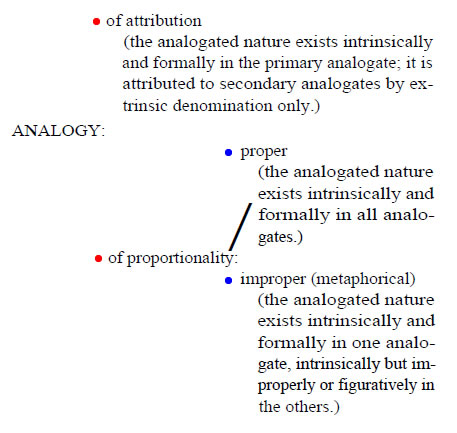

Before passing on now to the next particular, we present a sketch of analogy which shows the essentials of our discussion to date:

3. Unity and Abstraction of the Analogous Concept

This matter - in particular, the unity of the analogous concept - is of critical importance. A univocal concept, it will be recalled, has perfect unity or oneness of meaning. The analogous concept has no such unity; it is not, as we have seen, predicated according to a meaning that is absolutely the same in every case, but only partly the same and therefore partly different, too. Unity of some kind it must, however, have; otherwise it could not be predicated of different things according to a meaning that is in some way identical in each of them. The question of the unity of the analogous concept thus comes to this: how can a concept reduce a diversity to unity without excluding diversity altogether? Or, how can a diversity of things be brought under one concept when that concept must retain the diversity it seeks to unify? The question, let it be said at once, does not arise in metaphorical analogy, nor in that of attribution. In these there is not, as there is in proportionality proper, one concept which embraces all analogates; there is a plurality of concepts, specifically, a principal univocal concept which corresponds to the primary analogue and, for the derivative analogates, separate concepts but related to the principal concept. Health is predicated properly and univocally of animal. But the concept "health" does not cover "healthy food," "healthy medicine," and so on,; these have each its distinct concept but with a reference to the concept of the primary analogue.

In the analogy of proportionality, on the other handy which is the basic metaphysical analogy, we meet with a single analogous concept for all the analogates, and this because the nature (ratio) expressed by this concept exists intrinsically and formally in all of them. Thus, substance, quantity, quality, relation, and the other predicamental modes are each of them being, formally so, hence come under the unity of the notion of being. But then arises the question: how can the unity of a concept be truly maintained if it has at the same time to express a diversity, such as the diversity of being just mentioned?

Repetitious though it be, consider once more the case of the univocal concept, such as any generic notion. Here the unity or oneness of meaning is obvious. "Animal," for example, is a generic notion with a clearly determined meaning that applies in one and the same sense to everything of which it is predicated. The transition from the genus "animal" to its species is made, as we saw earlier, by adding the specific differences, which, and this is the point, are not actually included in the concept "animal." They are, however, included potentially, otherwise the generic notion could not receive them and thus be determined or contracted to its species. In short, the univocal concept is formally one and potentially divisible, hence potentially many.

The analogous concept also has unity, and it may also be diversified; but its unity is not the perfect kind of the univocal concept and its diversification is not effected by something from without - a circumstance best seen in the case of being, for what is not being is nothing. What this means is that the inferiors, or analogates, comprised under the analogous concept are intrinsic to it; consequently they are actually included and actually represented by the one analogous concept, but only implicitly so, or indistinctly; as when I see a multitude of men, I see them all and know they are all there without looking at any one of them in particular.21 The unity of such a concept is not that of an abstracted form, such as "animal" or "man"; rather, it is a proportional unity, founded on the real but proportional likeness which its analogated inferiors have to one another.22 To say, then, that the analogous concept is one means that it is proportionately one; so that its meaning is not absolutely identical from one inferior to another, but only proportionately so. That it cannot be absolutely identical is clear when you remember what the analogous concept embraces: all the diversities of its inferiors, though but implicitly and indistinctly. Of course, we can pass from this unified and undifferentiated concept (say) of being to more distinct concepts, namely by explicit consideration of the mode corresponding to a given analogate and thus making our knowledge of the analogate more distinct. But it need hardly be said that we shall also be passing from the general analogical concept of the analogate to a particular concept of the same analogate. So, the concept "being" represents all being and every mode of being - but none distinctly. We can make this concept more distinct and explicit by narrowing it, say to substance, or relation, or whatever predicament, even nonpredicament, as God and angels. But we shall have gone from the universal analogical concept of being to the far more restricted concept of one particular kind of being.

Metaphysics leans heavily on the analogous concept of the kind just analyzed; in fact, all its basic concepts are such. In this it differs markedly from other sciences, whose proper concepts are all univocal. This suggests, what is indeed true, that while metaphysics is by every canon a science, its scientific status is quite distinct, and its methodology will be similarly individual.

4. Order and Principle in Analogy

We have, to now, left hanging a topical matter on which the leading commentators of St. Thomas are not in complete agreement, namely whether every analogy requires a prime analogate. The analogy of attribution, it will be remembered, depends for its meaning on the secondary analogates being referred to a principal analogate, so that the latter is necessarily involved in the definition of the former. Of its very nature, then, this analogy implies an order of things in which there is some first thing as its principle, namely the primary analogate. Some authors, reiterating Sylvester of Ferrara, urge the question whether this characteristic should not be allowed to the analogy of proportionality as well. Lending considerable favor to the suggestion is the fact that St. Thomas, or so it seems, speaks equivalently of analogical predication and predication graded according to priority and posteriority (per Arius and per posterius). Every analogy, on this line of thought, would thus entail an order among its analogates, and if an order, then a principle or reference point upon which the order turns; which principle could be none other than a first analogate concretely determined.

In response, it can scarcely be denied that even in the analogy of proportionality there is a gradation, an order, hence some principle of order. But it is a fair question whether this principle is numerically and concretely one and thus a veritable first analogate, or whether it is only proportionately one, a principle of order arrived at through the assignment of relation among the analogates concerned. Take the prime example, the case of being, which, as we shall see, is analogous according to the analogy of proportionality. Can the analogy of being be established without explicit reference to the first being, that is, without going beyond the realm of the participated modalites of being? The answer, it seems to us, is yes; it is possible to conceive an analogous notion without respect to a first analogate; to have, in particular, an analogous notion of being which does not involve explicit reference to per se, or self-existent, being. But it is clear that such a concept will not be the final one; the more ultimate structure of the analogical order, of the order of being in particular, comes to light only in the measure that the unity of the analogical concept is grounded on the unity of a first term in reality. The metaphysics of being, in consequence, is not complete until created being is seen in its essential dependence on self- existent being, by very nature not dependent. Thus, while it is possible, in our opinion, to have an analogical concept of being without the concurrence of a first analogate, that there is such an analogate is not thereby denied; indeed, on this point all parties are in the affirmative but differ again on how it is arrived at, some taking the view that the analogy of proportionality suffices, others that recourse must be had to both analogies, proportionality and attribution. *Whatever the answer to that, it should be noted that in the analogy of attribution the first analogate, which is its principle of order, can be founded on more than one line of causality. St. Thomas usually points out three: material, efficient, and final causality, with the occasional addition of exemplary. It is therefore quite normal when for the same notion or reality there appear several orders, hence several principles, of analogy. The most notable instance is, once again, that of being. According to material or subjective causality the order of the modalities of being is based on their relation to substance, the first and absolute subject. This is the approach Aristotle adopts in the Metaphysics, namely the consideration of being as primarily substance. If, on the other hand, we view being from the standpoint of extrinsic causality (material or subjective causality is intrinsic), the first analogate will not be substance but must be sought in the being that is the ultimate cause of substance as well as of all other modalities of being, namely God, transcendent cause of all created being. This is the view St. Thomas usually takes, that is, the view of extrinsic causality, which, it must be admitted, is superior to the one of Aristotle in the Metaphysics; for in dealing with being from the standpoint of extrinsic causality we do not con sider it as subject but as esse, or according to its ultimate act - a notion to be more fully established in the chapter on essence and existence.23

Footnotes

12 Cajetanus, Thomas de Vio, De nominum analogia et de conceptu entis, edited by N. Zammit, O.P. (Rome: Angelicum, 1934). English translation and annotation by Edward A. Bushinski, C.S.Sp. and Henry J. Koren, C.S.Sp., The Analogy of Names and the Concept of Being (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1953; Duquesne Studies, Philosophical Series, 4). -- [Tr.]13 Joannes a S. Thoma, O.P., Cursus philosophicus thomisticus, IIa Pars Artis Logicae, q. 13, aa. 3-5; q. 14, aa. 2-3. Nova editio B. Reiser, O.S.B. (Turin: Marietti, 1948), Vol. I, pp. 481-99, 504-13. English translation available in The Material Logic of John of St. Thomas; trans. by Yves R. Simon, John J. Glanville, and G. Donald Hollenhorst (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1955), pp. 152-83, 190-208. -- [Tr.]

14 Sylvestris Ferrariensis, Commentaria in Summam Contra Gentiles, I, 34; in Opera Omnia S. Thomae Aquinatis, Leonine Edition (Rome, 1888- ). -- [Tr.]

15 Books, articles, and monographs which deal, in whole or in part, with the doctrine of analogy are legion, their number testifying to the critical role this notion plays in metaphysical speculation. Among the more readily available works in English are:

Anderson, James F., The Bond of Being (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Company, 1949).

Garrigou-Lagrange, Reginald, O.P., God: His Existence and His Nature, Vol. II, in particular pp. 203-224, 246-267, 453-455; trans. from the 5th French edition by Dom Bede Rose, O.S.B. (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Company, 1936).

Klubertanz, George P., S.J., St. Thomas Aquinas on Analogy (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1960). Not the least merit of Father Klubertanz's notable work, which appears under the Series "Jesuit Studies" and is subtitled "A Textual Analysis and Systematic Synthesis," is the carefully assembled Bibliography, which, while not pretending to be exhaustive of the subject, nevertheless runs through some ten pages (303-313).

Phelan, Gerald, St. Thomas and Analogy, Marquette Univesrity Aquinas Lecture, 1941 (Milwaukee: The Marquette University Press, 1948). An excellent introduction to the subject.

Not in English but now something of a classic is M. T.-L. Penido, Le role de l'analogie en théologie dogmatique; Bibl. Thom. XV, sect. theol. II (Paris: Vrin, 1931). These titles have been provided by the Translator.-- [Tr.]

16 In XI Metaph. lect. 3, no. 2197 (Rowan trans. II, 788). Because of its special relevance it may be well to cite the conclusion of the above quotation in St. Thomas' Latin: "In his vero quae praedicto modo dicuntur, idem nomen de diversis praedicatur secundum rationem partim eamdem, partim diversam. Diversam quidem quantum ad diversos modos relationis. Eamdem vero quantum ad id ad quod fit relatio."

17 In I Sent. d. 19, q. 5, a. 2, ad 1.

18 The Analogy of Names, chap. 1.

19 St. Thomas, loc. cit., "analogiam . . . secundum esse et non secundum intentionem."

20 De Verit. q. 2, a. IA c.

21 In Scholastic phrase the analogous concept is said to be derived by an abstraction "of confusion," meaning that the inferiors, while actually contained or represented in the concept, are not contained clearly or distinctly or explicitly but "confusedly," i.e. indistinctly or implicitly. -- [Tr.]

22 What is said in the text applies, of course, to every analogical concept. But since it is the notion of being that is most important in metaphysics, further illustration of its proportional unity may be to the purpose.

A concept, then, has unity if its meaning is unified or one. The analogous concept can have unity only if its analogates can be somehow unified under one formality. We have therefore to find that element in beings in which they are all somehow alike. If, then, with St. Thomas we define being as "that whose act is existence" (id cujus actus est esse), we shall have the common element, namely that in every being there is a relation or proportion of essence to existence. The concept of being is analogous because the relation of essence to existence is not identically the same in all beings but only proportionately the same. For example, existence is not realized in the same way in substance and accident, but both in substance and accident existence is proportioned to essence.

Briefly, the proportional unity of the analogous concept of being simply denotes that in all beings essence and existence are proportional to each other, without specifying any particular mode of proportion. All beings, accordingly, are alike in that all beings exist in proportion to their essence; and this is enough to give the notion of being a unified meaning. But this is not a perfect unity, or a perfectly unified concept; for then the proportion of essence to existence should have to be identically the same in all beings, which is ultimately to make all beings one - the doctrine of monism all over again. Still, we cannot think of being without thinking, at least implicitly, of the different ways in which this proportion of essence to existence is realized or realizable. Hence, the notion of being includes, implicitly yet actually, all the diversities of being. These remarks presuppose, to be sure, that being (as the text will shortly declare) is analogous by the analogy of proper proportionality. This analogy consists of a compound proportion, i.e. a proportion of proportions; e.g. 5:10 io: 20, etc. - only it must be remembered that the proportional equality of being is not an arithmetical equality. Now, we cannot think of the proportion 5:10, a proportion of doubleness, without thinking, at least implicitly, of the innumerable pairs of numbers that bear this proportion; indeed, the number is potentially infinite. Similarly, to repeat a point made above, we cannot think of the proportion of essence to existence without thinking, implicitly, of the many ways, the numberless ways, this proportion is realized or realizable. These infinitely varied proportions constitute the proportionality of being; and to think of the proportionality is to think, implicitly, of all the members of the proportionality. Hence, the notion of being includes, implicitly and indistinctly yet actually, all the diversities of being; but despite these diversities, all beings are alike so far as in all of them is realized the proportion of essence to existence. The concept of being expresses this proportional likeness; hence the proportional unity of the concept. -- [Tr.]

23 Namely chapter 7.